Screening in the Kinemathek Karlsruhe in May 2018

Paris, 1967: an upper-class family goes on vacation in the summer as usual for several weeks. In their apartment, a few young people open a kind of flat share and begin to practice for the world revolution. The individual persons correspond to certain ideological attitudes; we have the orthodox Marxist-Leninist, easily recognizable by his Lenin-style flat cap. He proclaims the wisdom of Marxist materialism in long speeches for which a seminar-like atmosphere is simulated. His opponents are the group’s two Maoists, Veronique and Guillaume (Meister); we should probably think of Goethe, one could also understand it to mean that the revolutionaries are currently completing their apprenticeship here. The two Maoists want to bring about the world revolution by force, that is, by exacerbating the social situation through acts of terrorism. And finally there is a “Mediterranean” looking young man who loves throwing bombs on itself, and thus serves the usual ideas of the anarchist.

The maid also lives in the apartment (played by Juliet Berto, who died much too early). In the group of young intellectuals, all of them coming from the bourgeoisie, who only play the revolution, she represents the only representative of the lower classes – anyone who still believes in the existence of classes would now say: She represents the proletariat. The would-be revolutionaries behave towards her like pubescent offspring of their upper-class parents. The maid’s bottom is patted, just like the male employer treats the staff who he thinks are available to him. So Godard decreed the young intellectuals in a subversive way: they are no different or better than their middle-class parents

Godard tells the film in a way that is anything but classic. We are dealing with a collage of cinematic techniques; several passages are filmed in a quasi-documentary manner; the actor / actress answers questions that we hear from off-screen, very faintly hinted at. Then the means of the theater are also used; so when the Vietnam War is portrayed more or less allegorically with toy airplanes. Photos of various people are faded in, as well as individual frames from comic strips, the range extends from Bertolt Brecht to Superman.

The China of Mao-tse Tung, in which the Cultural Revolution has raged since 1966, appears as a great model. Michael Endepols, who gave a wise introduction, asked if the Left (?) had not realized what was actually going on in China. In any case, the film does not give an answer to this question. And to attempt an answer from this historical distance would lead us very far away from Godard’s film. I will try anyway – but as an addition to this text.

The film has no conventional plot, Godard’s collage technique, one could also speak of iconoclasm, keeps the viewer in suspense, and the phrase-thrashing would-be revolutionaries is difficult to follow anyway.

In a long take, a train ride, Francis Jeanson, a French philosopher who practically plays himself, tries to rob one of the protagonists (Veronique, played by Anne Wiazemsky, then Godard’s wife) of her adventurous illusions. She is the Maoist par excellence, wants to close the universities, send the students to the country to harvest potatoes and force the beginning of the revolution with individual acts of terrorism.

So it is Veronique who commits an act of terror at the end of the film, but she makes a terrible mistake.

One can confidently understand this as Godard’s comment on Maoism and the Cultural Revolution.

As seen today, Godard’s film is a document of the times in two respects: it shows what was going on in some revolutionary minds and which erupted a year later.

And it is a document of film history, because nowadays films of this kind are no longer made, which wildly mix the means of the most diverse genres. The references to Brecht finally make me think of an anecdote: a play was rehearsed in a provincial town, and the leading actress, who knew Brecht personally, insisted on alienation (Verfremdung). There was a dispute with the director, and finally the master had to travel from Berlin. He looked at a rehearsal and became clear. The main actress got to hear that she should play theater and not alienation. Somebody should have said that to Godard too.

Written on May 26, 2018 and 2020 slightly revised, slightly added in 2021.

And now a dive into memory.

Only a heavily embellished image of the cultural revolution penetrated the outside world, that is, to Europe, for which the propaganda apparatus of the People’s Republic of China provided in an exemplary manner. That still happened years later through publications like the “Peking Look Around” (german: Peking-Rundschau) or “China in the Pictured” (german: China im Bild). So one got the impression that bourgeois elements in particular, which had persisted in Chinese society, would now be finally eliminated. Only, one wonders today, what does this “eliminate” mean. We in Germany and probably in all of Europe within the left did not give any thought to that. We had no idea what it really meant: For example, the closure of universities for many years, the closure of the Beijing Film School, the arrest and detention of people who for example owned a violin or some other musical instrument that the hordes of young party members, called the “Red Guards”, considered as “western kind of living”. This is an arbitrary example and innumerable ones could still be listed: the destruction of Buddhist and other temples down to the last village, the destruction of numerous historical cultural assets, etc. etc. What happened to those arrested was not made public It was said that they were being sent to the countryside for re-education. Sounds very nice. One cannot imagine it, often a certain percentage, let’s say, of the workforce of a company was arrested. If the party official in charge said on one day that it was 5% of the workforce, 5% were arrested. If he came to the revolutionary realization a day later that it would be more like 10%, then people were arbitrarily arrested again until the quota was reached. Forgive me for the irony. Those arrested were interned in remote provinces, for example in the Gobi desert, where a large part in the camps starved to death. Chinese director Wang Bing has made some harrowing films about these camps and locations, for example “The Ditch” (2010).

The Cultural Revolution left its mark on Chinese society that we can hardly understand and assess in its full extent. It left its mark on every individual that it suffered and endured. It was brainwashing not only for those who came to the camps. At this point I would like to insert an anecdote from my personal experience. In the course of my work as managing director of the Student Cultural Center, the Association of Chinese Students in Karlsruhe regularly organized Chinese Spring Festivals in the student house. The cultural attaché of the Consulate General in Frankfurt came regularly, and every year it was a different diplomat. Continuity of work don’t seem to matter to Chinese diplomacy. So one day an older man appeared as a cultural attaché wearing a plastic leather jacket and corduroy trousers. If you did the math, it became clear that he must be a member of the generation that had consciously witnessed the Cultural Revolution. He read his speech, interrupted it regularly, looked into the audience and clapped his hands himself. So the audience knew when to clap – and clapped obediently. This is what the result looks like when people are socialized like in the cultural revolution. I have seldom experienced a more grotesque self-humiliation. And of course it affects both sides – the speaker as well as his audience.

In Germany there were still admirers of the People’s Republic of China many years later. They delighted in the “Hundred Flowers Campaign” of the 1950s or the “Big Leap”. They simply did not want the totalitarian character of this communist regime to be true. For me personally, the so-called “First Generation” films played a major role in understanding the true character of the communist regime in the People’s Republic of China. The “first generation” refers to those film directors who received education after the Beijing Film School reopened; for example Zhang Yimou, who then shot the very strong film “Life!”, which often demands the viewer to the limit of the endurable, and Chen Kaige, who created with the film “Farewell, my concubine” one of the great masterpieces of the Chinese film.

The last section was written in October 2020.

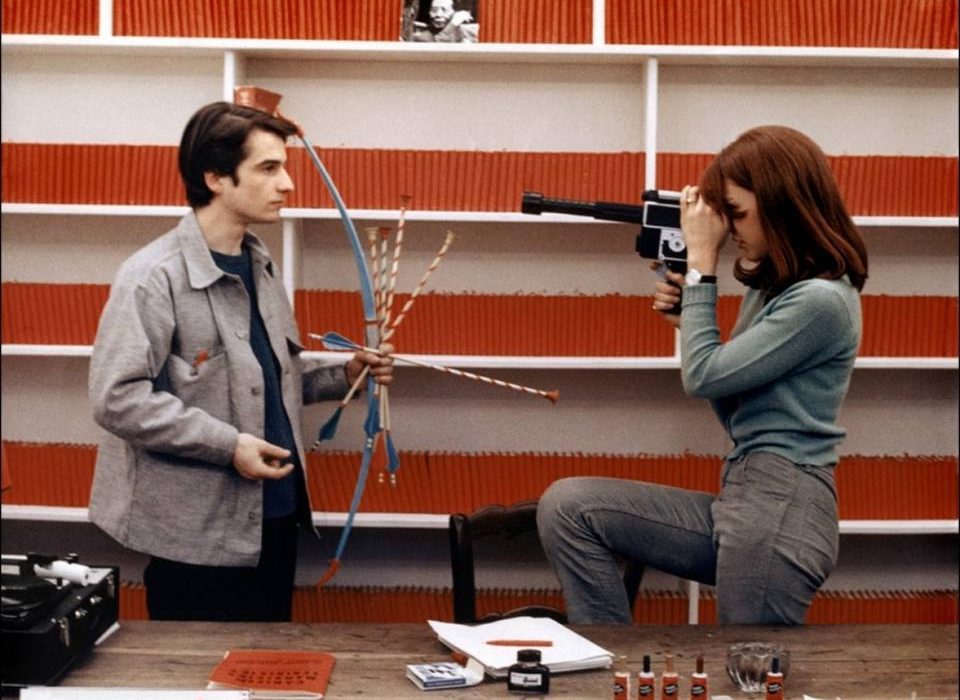

Photo: Anne Wiazemsky and Jean-Pierre Léaud in “La Chinoise” by Jean-Luc Godard.