Some basic thoughts on genre film, especially german genre film – but still no theory of genre film. To be more precise, I am concerned with the relation of the genre film to external reality.

This text was created after I saw the documentary by Dominik Graf and Johannes F. Sievert “Open Wound German Film” on February 8, 2021 on ARTE. However, the documentation only triggered something for me that I had wanted to put on paper for a long time.

I would like to emphasize right from the start that I admire Dominik Graf for many of his films, which are often drastically direct in their subject matter and in their pictures. I still consider “In the Face of Crime” to be the best German TV series since Fassbinder’s “Berlin Alexanderplatz”. For the average German television viewer it was probably too complex or perhaps confronted him with too much foreignness: not only settled in the milieu of the Russian mafia in Berlin, but also because of the ethnic origin of Jews; So Jewish Russian mafia. Twice as strange, one could say. In the middle of Germany and yet very little German. I’m not sure if this explanation is true, but maybe a possible answer to the question of why this series was so unsuccessful on German television.

I would like to contribute a few thoughts on an aspect that Sievert and Graf’s documentation could not take up because it is about a theoretical question that cannot be portrayed and discussed in a film. This is only possible in a text because the discussion of theoretical questions can only take place in this way.

I’m concerned with the relationship between the film, one could also generally say a work of art, to external reality, to the social environment. I would like to address the question of how the film accesses external reality. And then it is only logical if, following the initial question, one considers which “seat in life” viewers give the film.

I would like to discuss these questions using the example of films that represent an extreme in their access to external reality: the so-called genre films. But before I get straight to the genre film, a few preliminary considerations.

Every film, every work of art invents its own world, and is or becomes part of the already existing real world through its creation. The film as the product of a creative process, or thought to be expanding, the work of art, offers a sensual – aesthetic – and no cognitive access to the world, to external reality.

For this aesthetic access to the world, the film, the work of art, has to invent forms; in film, it is moving images that represent this access. Not every film reinvents these forms, on the contrary, many films, many works of art fall back on existing forms. This is actually quite natural, because the recipients have to know the forms in which the film and artwork pour their objects, because without knowledge of these forms and their meaning, the recipients would not understand the films or the works of art. However, the more films or works of art make use of the existing and often long-standing forms, the more conventional they become. Such conventional products run the risk of boring audiences. So there is a first demand for a certain innovation of the forms, which, however, is purely inherent in art.

The second demand for innovative forms arises from the constant changes in external reality. In order to be able to shape the incessant developments and changes in external reality, the existing creative means, i.e. the forms of the work of art, have to be continually renewed. Because only updates and further developments of the forms make the constant changes of the real world tangible.

So it is a dialectic that determines the relationship between the work of art, the film, and external reality – and often also the quality of the work of art.

What do all these theoretical lines of thought have to do with genre cinema? Well, my thesis on genre cinema is: In genre cinema the dialectic described has little or no effect because genre cinema tends to ignore external reality and only “relate” to its own formal language. And that explains the concept of the title of this text: The genre cinema does not produce any original images in its effort to grasp and understand external reality, but only images of found images – in other words, decals. The visual worlds of genre cinema have as much to do with external reality as a decal as a decal has to do with the original photo or image that it is supposed to represent. And the stronger this tendency of genre cinema becomes, the duller and less interesting these decals become. Because the decals cannot react to changes and innovations in external reality, because they have no poetic means at their disposal; they only know the aesthetic means of the images they find.

This inability to grasp and deal with real life often even extends to the content-related aspects. That brings me back to the documentary by Sieverts and Graf: In quite a few homeland films, there are only professions that are actually out of date: the film retreats into the woods, where the forester goes on the prowl.

For a short time these films were able to take advantage of the unspoken wish of many Germans to escape from reality – but only for a short time. .And it is almost inevitable that these films did not become great classics of international cinema, just as the directors of these films did not achieve great careers. And so the genre cinema of the 50s is an “open wound” of German film and can stand for the inability to make films that are state-of-the-art that could have helped to grapple with this time.

Consequently, the documentary describes films and the biographical fate of some directors, none of whom can boast great successes The Heimatfilm, which in its forms goes back not a little to the cinema of the Nazi era, is then a genre cinema of a very German kind. However, you are welcome to add that almost every country develops its own forms of genre film, and maybe you should think about why the spaghetti western was born in Italy.

But let’s stay with Heimatfilm. In my opinion, precise access and a detailed interpretation of certain films would make it possible to strike one or two small sparks of knowledge, so that it could be shown that some films do not portray as pathetic restorative conditions as they often appear. Unfortunately, unfortunately, Olaf Möller also missed the opportunity in the documentary by Sieverts and Graf to use the historical distance to establish connections between film history and developments in society as a whole. He doesn’t manage to do more than a couple of pretty bon mots.

He explicitly refers to a film that is at a turning point in the post-war period. I would like to explain this briefly. This historical connection became clear to me when researching a program for the fifties that was shown a long time ago by the Karlsruhe Municipal Cinema and that I largely curated. The first post-war years were socially characterized by a profound pessimism, which was also reflected in the films. It was the time of the so-called “rubble films”. One of the last films that consistently didn’t offer the viewer a happy ending, but rather the worst possible outcome, was the scandalous film “The Sinner” (OT: Die Sünderin) with Hildegard Knef. The main characters are broken people, often drug addicts, more or less criminal, and if it’s just the black market, etc. etc. The film ends in a suicide. Only a few months after this film, “Rape on the Moor” (OT: Rosen blühen auf dem Heidegrab – exact translation: Roses bloom on the grave in the Heather) came to the cinema. The film is about a crime and an alleged repetition in the usual moor legend. However, the film doesn’t end with a new crime – it gives the audience a happy ending. The film can be understood as a seismograph of the changed social mood in a young Federal Republic of Germany, which is embarking on an economic miracle. It is remarkable that this paradigm shift took place within a very short time. The premieres of the two films were only a few months apart. It should also be the task of film historiography to recognize such connections and make them accessible in the retrospective. Unfortunately, Olaf Möller does not go into this, but only presents images from the film that show his relationship to genre cinema.

One may wonder whether a certain approach to “wound healing” can be found here after all. If you look closely.

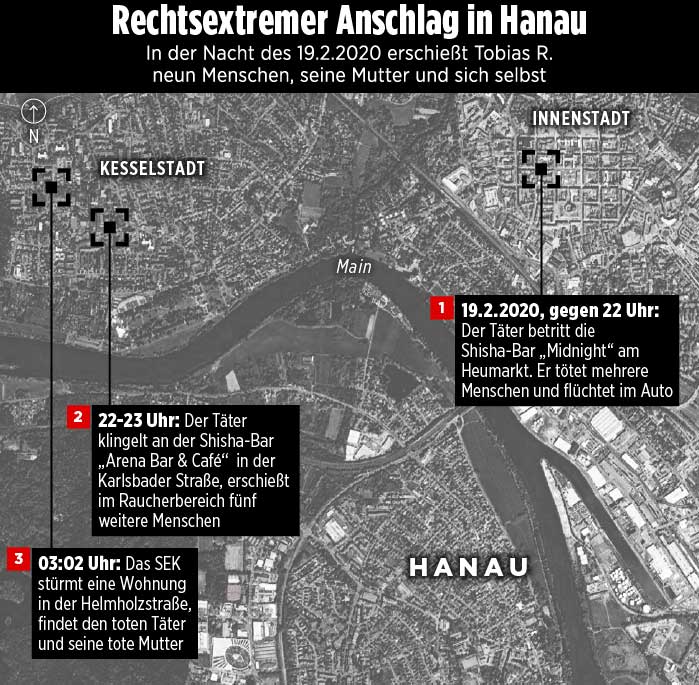

Given the current situation, I myself have doubts about this optimistic statement about German film. I’m talking about the film that Uwe Boll made about the Hanau attack. Perhaps that is already wrong, and one should rather say that Uwe Boll uses the assassination attempt to functionalize it for a genre film. He doesn’t have to worry so much and think up some terrible crime. I don’t even want to address whether, as he claims, he contacted the relatives of the victims or not. That is not my concern, although I would have understanding for the victims’ relatives who would have strictly refused any contact with Uwe Boll if they had dealt with the person Uwe Boll and his work even very superficially.

And to say it right away: I haven’t seen the film (yet). In the following, I am based on the statements by Claudius Seidl in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung of April 17, 2021 What I said above about genre cinema is precisely true for Uwe Boll’s film: he does not find any original images for this terrible crime and to capture the extent of the horror. Uwe Boll fires blank cartridges and injects theater blood, and that remains, just as Claudius Seidel writes: harmless. Here the boundless poverty of genre cinema becomes clear, which Uwe Boll celebrates.

Incidentally, Boll has dealt extensively with genre cinema and its stylistic devices: he has a doctorate on it and one can assume that he is aware of the questionable craft he indulges in.

Films like this one are made for an audience that bursts into dull roar when the blank cartridges pop and the theatrical blood spurts. Boll functionalizes the Hanau assassination attempt for his film, what happened is only welcome material for him. He has no moral scruples. Not only is Boll the worst director some call him, he’s a terrible director too.

Boll deepens the wounds in German film history; he really fires up with his films and tears open new wounds. “Let it bleed” is probably his motto.

* Decal: according to Duden, “Image that is mirror-inverted on a water-soluble primed paper and can be transferred to an object after moistening, whereby the paper is peeled off.”

Aerial view: Google Earth Pro