(Segue testo in italiano)

Following the article “The most beautiful film museum in the world” published here on Sinn und Cinema, I can say that, from my point of view too, the Mole is indeed the most beautiful cinema museum in the world, as well as a building that followed truly unique path. My opinion could be biased, as I was born and raised in Turin. Certainly, though, arguments that support this evaluation are not missing. To complete the “internal” perspective on the Museum previously proposed in Josef Jünger’s article, here I will analyze the Cinema Museum from an “external” point of view, that is, in its intrinsic relationship with the Mole, with the city of Turin and with the history of cinema.

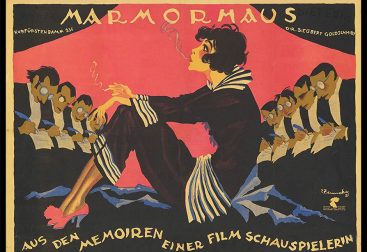

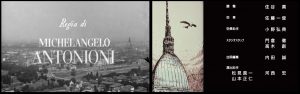

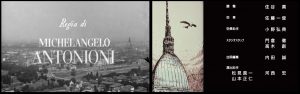

First of all, it is important to stress that Turin is a city that not only saw the birth of Italian cinema, but was and still is the source of inspiration for countless films throughout the history of cinema: let’s take for instance the colossal “Cabiria” (1914) by Pastrone and “Maciste all’Inferno” (1925) by Brignone; the emblematic opening sequence of “Le Amiche” (1955) by Antonioni; the films of the master of horror Dario Argento shot in particular on the foggy hills of Turin; Mastroianni’s trip to Turin in Tornatore’s film “Stanno tutti bene” (1990); or the commedia all’italianaby Risi “Profumo di donna” (1974). Not to mention “Dopo Mezzanotte” (2004), already well described by Josef Jünger, or the cult film shot entirely in Turin “The Italian Job” (1969) with Michael Caine. A peculiar homage to Turin, and precisely to the Mole Antonelliana, is even found in the titles of “Porco Rosso” (1992) by Studio Ghibli.

In this scenario strongly oriented towards the seventh art, the Mole is the real protagonist, and with it the Cinema Museum. But the Mole is not “just” a museum. The Mole is the identity symbol of the city of Turin. And how many cities in Italy boast a museum (of cinema) as a city symbol, especially in Italy, where the symbols tend to be religious? For instance, take the the Domes of Milan and Florence, the Cathedrals of Palermo and Genoa, the Basilica of Venice. The Colosseum and the Leaning Tower of Pisa might be exceptions, but Rome is an exception per se, and in Pisa’s Piazza dei Miracoli, the Tower is known to be in good company. However, no city is symbolized exclusively by a museum. To push this idea further, I would dare to say that the peculiarity of Turin lies precisely in being symbolized by its museums because, alongside that of cinema, the Egyptian one also stands out. With all respect and admiration for the Turin Cathedral, the Basilica of Superga* or the Reggia di Venaria**, I think that the two aforementioned museums play a predominant role in terms of tourism and city identity. And between the two, in general, the added value of the Mole is evident: the Mole mirrors Turin.

This building is a true identity mirror of the Piedmontese capital. Several years ago the project for the construction of the first skyscraper in Turin was presented, by Renzo Piano. It is known that in Italy bricks, pebbles and tiled roofs are loved, but modern society requires construction of another kind. At the time, a committee called “Let’s not scratch the sky of Turin” was born to oppose the project and not to pollute the elegant Turin skyline, with the solitary Mole standing out between the hills and the Alps. The group did not succeed in blocking the construction of the skyscraper, but obtained a result that I consider symptomatic of the link between Turin people and the Mole Antonelliana: the skyscraper project was adapted to make it lower than the Mole. A few meters, but very significant. This anecdote is engraved in my memory and speaks clearly: the Mole is the only building that, at least for now, is allowed to “scratch” the sky of Turin. The skyscraper was then built, moreover in a fairly central area, and a second one came later by Fuksas. Despite their imposing structure, the two skyscrapers do not replace the Mole either on an aesthetic level, much less on a conceptual level: its profile remains unique and embodies the sober style and Turin’s cultural inclination.

Thinking back to the path of the building, I find it particularly interesting how it has continuously evolved since the nineteenth century, as if the building had been in search of its own identity. And even surviving the bombings of 1942 and various natural disasters. Until 1904, in fact, the Mole was the tallest masonry building in Europe. At the top stood a statue depicting the “Winged Genius”, one of the symbols of the House of Savoy, until a hurricane caused it to collapse. The statue was thus replaced by a 12-pointed star, but in 1953 a powerful storm destroyed almost the entire spire, and with it the star. The Antonioni film mentioned above, moreover, is a real testimony of this “beheading” of the Mole. Finally, since 1961, a new star has dominated the top of the Mole, a dodecahedron which since 2020 has also become the official symbol and award of the TFF – Torino Film Festival.

The “Stella Award for artistic innovation” of 38 TFF was awarded to Isabella Rossellini, a multifaceted artist – like the symbol itself. A spot is dedicated to the Star, as well as a short socumentary (attached at the end of the text) that tells the story through splendid vintage photos. The TFF 2020 this year had to be held online. Particular importance was given to the issues of gender equality and interculturality, both at the level of films offered and at the level of administration; the jury of the international sections of the TFF, in fact, was entrusted to professional women of the sector and of Japanese, Syrian and Persian nationality, alongside the Italian ones. A quick look at the nationalities of the Festival’s winning films confirms this intercultural openness.

This openness to the diversity and interculturality of the city of Turin is also evidenced by the relatively recent use of the Mole building in terms of social communication. At the city level, if not by now national and international, the Mole has in fact become a real participatory vehicle of information and culture. As if he were a medium. These dynamics probably date back to two key elements in the history of the Piedmontese capital: first of all the artistic event “Luci d’Artista”, which started in Turin in 1998 at the suggestion of the then councilor for the promotion of the city, Fiorenzo Alfieri; secondly, the XX Winter Olympics, held in Turin in 2006. The Olympics have given an extraordinary impetus to the growth of the city in the tourist-cultural direction, allowing it to break free, at least in part, from the image of industrial-automotive Turin.

The splendid initiative of the “Luci d’Artista” deserves particular attention, as it is closely interconnected with the Mole, with the Cinema Museum, and now with Turin and Italian film history. The “Lights” are an itinerant and interactive event that has been lighting up and coloring the Turin landscape during its gray winters for more than 20 years. One of the few fixed lights is the one installed on the side wall of the Mole in early winter, created by the artist Mario Merz: “The flight of numbers”, or a reproduction of the prime numbers of the Fibonacci series. The idea of progression intrinsic to the series of the Tuscan medieval mathematician reflects the idea of growth, development and ascension already inherent in the Mole. To this scientific-cultural impulse is added the role of cultural vehicle that the Mole has assumed in recent times. The headquarters of the National Cinema Museum, in fact, is used more and more often to promote significant initiatives, commemorate personalities or events, pay homage to particular days, all through mono or multi-color projections on its four sides: orange for the day. against racism, the blue for autism day, the classic lights for Christmas, the flags of France and Belgium for their respective attacks, the grenade for the Superga massacre, the red against the death penalty – and many other wonderful projections of which I am attaching some images: the symbol of the 2006 Winter Olympics; a piano complete with musical reproductions on the occasion of the death of Ezio Bosso, the late Turin musician; the tricolor for the 150th anniversary of the unification of Italy in 2011 and then as moral support during the lockdown in March and April 2020. Then there are initiatives such as the one on the occasion of Morricone’s death in the summer of 2020: for two weeks, a hour a day, some of his best soundtracks have been broadcast in the pedestrian area around the Mole.

Last but not least, on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the Cinema Museum, whose foundation is due to the historian of Italian cinema Anna Maria Prolo, iconic scenes from the history of cinema were projected onto the Mole with the technique of videomapping, curated by Donato Sansone. This light installation resulted in an intense homage to cinema as art, a message of pure cinephilia transmitted through the faces and scenes of Sophia Loren, Marcello Mastroianni, Ornella Muti, Vittorio Gassman, Sergio Leone, Federico Fellini, and international icons such as Indiana Jones, King Kong, James Bond, Darth Vader, Wall-E.

The Mole, which has always been an artistic and visual reference point for those walking the streets of Turin or visiting the city, has now also embraced an orientative function at a more abstract level and, undoubtedly, with a mediatic character. Between visual projections and acoustic reproductions, it can be said that the Mole is a real cinema en plein air.

Turin, Mole, Cinema: an indissoluble union, one of a kind.

Written and translated by

Maria Adorno

* Basilica Superga: pilgrimage church near Turin.

** Reggia di Venaria: large palace ensemble of the Piedmontese ruling house from the 17th century in the surroundings of Turin.

Cover photo: ©torino.corriere.it

_______________________________________________________________________

Facendo seguito all’articolo “Il più bel museo del cinema del mondo” pubblicato qui su Sinn und Cinema la scorsa settimana, posso affermare che, anche dal mio punto di vista, la Mole è effettivamente il museo del cinema più bello del mondo, nonché un edificio dal percorso più unico che raro. Il mio parere potrebbe essere di parte, essendo io nata e cresciuta a Torino. Di certo però gli argomenti a favore di questa valutazione non mancano. A completare lo sguardo “interno” al Museo proposto precedentemente nell’articolo di Josef Jünger, qui analizzerò il Museo del Cinema da un punto di vista, per così dire, “esterno”, e cioè nel suo intrinseco rapporto con la Mole, con la città di Torino e con la storia del cinema.

Innanzitutto, è importante sottolineare che Torino è una città che non solo ha visto nascere il cinema italiano, ma è stata ed è ancora fonte d’ispirazione di innumerevoli film nel corso dell’intera storia del cinema: si pensi al colossal di Pastrone “Cabiria” (1914) e a “Maciste all’Inferno” di Brignone (1925); all’emblematica sequenza iniziale di “Le Amiche” (1955) di Antonioni; ai film del maestro dell’horror Dario Argento girati in particolare sulla nebbiosa collina Torinese; al viaggio a Torino di Mastroianni nel film di Tornatore “Stanno tutti bene” (1990); alla commedia all’italiana di Risi “Profumo di donna” (1974). Per non parlare di “Dopo Mezzanotte” (2004), già ben descritto da Josef Jünger o del film cult girato interamente a Torino “The Italian Job” (1969) con Michael Caine. Un peculiare omaggio a Torino, e proprio alla Mole Antonelliana, si trova perfino nei titoli di “Porco Rosso” (1992) dello Studio Ghibli.

In questo scenario fortemente orientato alla settima arte, la Mole è la vera protagonista, e con essa il Museo del Cinema. Ma la Mole non è “solo” un museo. La Mole è il simbolo identitario della città di Torino. E quante città in Italia vantano come simbolo cittadino un Museo (del cinema), soprattutto in Italia, in cui i simboli sono tendenzialmente di carattere religioso? Si pensi ai Duomi di Milano e Firenze, alle Cattedrali di Palermo e Genova, alla Basilica di Venezia. Il Colosseo e la Torre di Pisa potrebbero fare eccezione, ma Roma fa eccezione di per sé, e in Piazza dei Miracoli a Pisa si sa che la Torre è in buona compagnia. Ad ogni modo, nessuna città è simboleggiata esclusivamente da un Museo. Volendo spingere oltre questa idea, oserei dire che la peculiarità di Torino sta proprio nell’essere simboleggiata dai suoi musei perché, a fianco a quello del cinema, anche quello Egizio spicca. Con tutto il rispetto e l’ammirazione per il Duomo di Torino, la Basilica di Superga o la Reggia di Venaria, penso che a livello turistico e di identità cittadina i due suddetti Musei abbiano un ruolo preponderante. E tra i due, in generale, il valore aggiunto della Mole è evidente: la Mole rispecchia Torino.

Questo edificio è un vero metro identitario del capoluogo piemontese. Diversi anni fa è stato presentato il progetto di costruzione del primo grattacielo di Torino, ad opera di Renzo Piano. Si sa che in Italia si amano i mattoni, i ciottoli e i tetti in tegole, ma la società impone costruzioni d’altro genere. All’epoca nacque un comitato chiamato “Non grattiamo il cielo di Torino” che si oppose al progetto per non inquinare l’elegante skyline torinese, con la Mole solitaria a stagliarsi tra collina e Alpi. Il gruppo non arrivò a bloccare la costruzione del grattacielo, ma ottenne un risultato che io giudico sintomatico del legame tra torinesi e Mole Antonelliana: il progetto del grattacielo venne adattato in modo da renderlo più basso della Mole. Pochi metri, ma molto significativi. Questo aneddoto è scolpito nella mia memoria e parla chiaro: la Mole è l’unica costruzione a cui, almeno per ora, si permette di “grattare” il cielo di Torino. Il grattacielo fu quindi costruito, per altro in zona abbastanza centrale, e a seguire ne arrivò anche un secondo ad opera di Fuksas. Nonostante la loro struttura imponente, i due grattacieli non sostituiscono la Mole né a livello estetico, né tanto meno a livello concettuale: il suo profilo resta unico e incarna lo stile sobrio e l’inclinazione culturale torinese.

Ripensando al percorso dell’edificio, trovo particolarmente interessante come si sia continuamente evoluto dal XIX secolo, quasi la costruzione fosse stata alla ricerca della propria identità, sopravvivendo perfino ai bombardamenti del 1942 e a svariati disastri naturali. Fino al 1904, infatti, la Mole era la costruzione in muratura più alta d’Europa. In cima troneggiava una statua raffigurante il “Genio Alato”, uno dei simboli di Casa Savoia, finché un uragano non lo fece crollare. La statua venne così sostutuita da una stella a 12 punte, ma nel 1953 un potente temporale distrusse quasi tutta la guglia, e con essa la stella. Il film di Antonioni citato precedentemente, per altro, è una vera e propria testimonianza di questa “decapitazione” della Mole. Dal 1961, infine, in cima alla Mole troneggia una nuova stella, un dodecaedro che dal 2020 è diventato anche simbolo ufficiale e premio del TFF – Torino Film Festival.

Il “Premio Stella per l’innovazione artistica” del 38 TFF è stato conferito a Isabella Rossellini, artista poliedrica – come il simbolo stesso. Alla Stella sono dedicati uno spot, nonché un breve documentario (in allegato a fine testo) che ne narra la storia attraverso splendide foto d’epoca. Il TFF 2020, che normalmente ruota attorno alla Mole, al Cinema Massimo, e a molti altri luoghi diffusi sul territorio e legati al cinema, quest’anno si è dovuto svolgere online. Particolare rilevanza è stata data alle tematiche di gender equality ed interculturalità, sia a livello di film proposti sia a livello di amministrazione; la giuria delle sezioni internazionali del TFF, infatti, è stata affidata a donne professioniste del settore e di nazionalità giapponese, siriana e persiana, accanto a quelle italiane. Uno sguardo rapido alle nazionalità dei film vincitori del Festival conferma quest’apertura interculturale.

Quest’apertura alla diversità e all’interculturalità della città di Torino è testimoniata anche dall’uso, relativamente recente, che viene fatto dell’edificio-Mole in chiave di comunicazione sociale. A livello cittadino, se non ormai nazionale et internazionale, la Mole è infatti diventata un vero e proprio veicolo partecipativo d’informazione e cultura. Quasi fosse un medium. Queste dinamiche risalgono probabilmente a due elementi cardine della storia del capoluogo piemontese: in primis la manifestazione artistica “Luci d’Artista”, avviatasi a Torino nel 1998 su suggerimento dell’allora assessore alla promozione della città, Fiorenzo Alfieri; in secondo luogo, le XX Olimpiadi invernali, svoltesi a Torino nel 2006. Le Olimpiadi hanno dato un impulso straordinario alla crescita della Città in direzione turistico-culturale, permettendole di slacciarsi, almeno in parte, dall’immagine della Torino industriale-automobilistica.

La splendida iniziativa delle “Luci d’Artista” merita particolare attenzione, in quanto strettamente interconnessa con la Mole, con il Museo del cinema, nonché ora con la storia cinematografica torinese ed italiana. Le Luci sono una manifestazione itinerante ed interrativa che illumina e colora il panorama torinese durante i suoi grigi inverni da ormai più di 20 anni. Una delle poche luci fisse è proprio quella che viene installata sulla parete laterale della Mole a inizio inverno, creata dall’artista Mario Merz: “Il volo dei numeri”, ovvero una riproduzione dei numeri primi della Serie di Fibonacci. L’idea di progressione intrinseca alla Serie del matematico medievale toscano rispecchia l’idea di crescita, sviluppo e ascensione già proprie della Mole. A questo impulso scientifico-culturale si aggiunge il ruolo di veicolo culturale che la Mole ha assunto negli ultimi tempi. La sede del Museo Nazionale del Cinema, infatti, viene usata sempre più spesso per promuovere iniziative significative, commemorare personalità o eventi, omaggiare giornate particolari, il tutto tramite delle proiezioni mono o pluri-color sui suoi quattro lati: l’arancione per la giornata contro il razzismo, il blu per la giornata dell’autismo, le classiche luci per Natale, le bandiere di Francia e Belgio per i rispettivi attentati, il granata per la strage di Superga, il rosso contro la pena di morte – e molte altre meravigliose proiezioni di cui allego alcune immagini: il simbolo delle Olimpiadi invernali nel corso del 2006; un pianoforte con tanto di riproduzioni musicali in occasione della morte di Ezio Bosso, compianto musicista torinese; il tricolore per il 150° dell’unità d’Italia nel 2011 e poi come sostegno morale durante il lockdown di marzo ed aprile 2020. Si aggiungono poi iniziative come quella in occasione della morte di Morricone nell’estate 2020: per due settimane, un’ora al giorno, nella zona pedonale tutt’attorno alla Mole sono state trasmesse alcune delle sue migliori colonne sonore.

Dulcis in fundo, in occasione del 20esimo anniversario del Museo del Cinema, la cui fondazione si deve alla storica del cinema italiano Anna Maria Prolo, sono state proiettate sulla Mole delle scene iconiche della storia del cinema con la tecnica del videomapping, a cura di Donato Sansone. Quest’installazione luminosa è risultata in un intenso omaggio al cinema in quanto arte, un messaggio di pura cinefilia trasmesso attraverso i volti e le scene di Sophia Loren, Marcello Mastroianni, Ornella Muti, Vittorio Gassman, Sergio Leone, Federico Fellini, e icone internazionali quali Indiana Jones, King Kong, James Bond, Darth Vader, Wall-E.

La Mole, da sempre punto di riferimento artistico e visivo per chi cammina per le vie di Torino o visita la città, ha ora abbracciato anche una funzione di orientamento a livello più astratto e, indubbiamente, d’impronta mediatica. Tra proiezioni visive e riproduzioni acustiche, si può dire che la Mole sia un vero e proprio cinema en plein air.

Torino, Mole, Cinema: un connubio indissolubile, unico nel suo genere.

Maria Adorno

[fvplayer id=”2″]